Combining BIM and GIS for a Sustainable Society

Community-scale Assessment of Energy Performance

Nikken Sekkei Research Institute in Tokyo, Japan, has developed a vision for cities to help them choose an energy optimisation strategy for neighbourhoods comprising a variety of building types. The optimisation of energy consumption is approached from an area-wide standpoint. The added value of the method for city renewal programmes has been demonstrated based on a central district in the Japanese capital.

Japan has low energy resources and a high population density. That provides extra stimulation to develop ecofriendly urban planning. City and environmental designs use low carbon footprint solutions as their starting point, and planners, urban designers, architects, engineers and landscape specialists work together to provide integrated solutions. Urban energy supply and demand is an important item in this context of smart city management. It is a far more complex system than a single building since there are synergies between various elements like transport and the city infrastructure. Especially in Japan’s largest cities, that infrastructure is becoming more and more compact.

Transit-oriented发展

According to the latest forecasts, more than a quarter of Japan’s citizens will be aged over 65 in 2055. By then, the population will also have shrunk from the current 127 million to 90 million. In Tokyo (13 million people), one in four elderly citizens live alone with no family to take care of them. The predicted population growth in the 65-and-over group is one of the reasons that, for the past two decades, city planning has been based on compact, multifunctional neighbourhoods concentrated around the public transport system. Japan has no choice but to invest in developing such infrastructure rather than controlling road traffic.

Tokyo Metropolitan City is huge, but the scale has remained human in its neighbourhoods since Tokyo opted for the transit-oriented development (TOD) concept. Most people live no more than 1,000 metres from a train station. In these communities, everything is within walking distance: shops, offices, public facilities, parks and green spaces, and of course transport. “It helps people of all ages to live independently in their own homes and communities. It also saves emissions by vehicles and contributes to mitigating the production of greenhouse gases,” elucidates Mr Shinji Yamamura, executive officer at the Nikken Sekkei Research Institute. Reducing CO2对东京非常重要。这座城市是城市热岛的典型例子。在过去的一个世纪中,年平均温度增加了约3ºC(5.4ºF)。与2000年的水平相比,市政当局希望将温室气体排放量减少25%。因此,在过去十年中,该市不仅创造了一千公顷的新绿色空间,而且还需要减少能源在运输和建筑物中的消费。

Low-energy buildings

Tokyo’s urban infrastructure evolved during the city’s period of rapid economic growth, and now requires renewal. Of course, energy saving is part of the plan. Mr Yamamura explains: “New buildings will be recommended, but net zero-energy buildings (ZEB) are not always possible. That is especially so in renovation. Much larger investments are needed than when one aims at the more common level of low-energy buildings. And even for that level, owners of very large commercially exploited buildings can perhaps generate enough budget, but it is still very difficult for the owners of small to medium-sized buildings.” Nevertheless, it is necessary. In 2014, the average annual energy consumption in Japan’s commercial buildings was around 2,140 to 2,450MJ/m2, in office buildings it was 1,457MJ/m2, in hospitals it was 2,952MJ/m2and in residential buildings it was 778MJ/m2.

These elements – community infrastructure, renovation needs, energy reduction policies –inspired the researchers to develop a flexible strategy to renovate all the buildings in a neighbourhood as energy-efficiently and as pragmatically as possible, instead of each building on its own. It is the overall result for Tokyo that counts. Minimising the range of the infrastructure to be renewed would also reduce the initial costs.

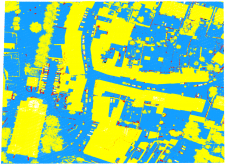

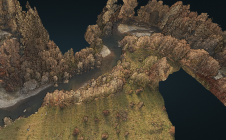

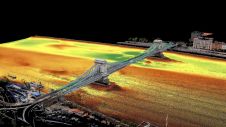

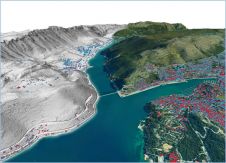

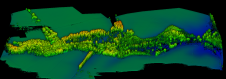

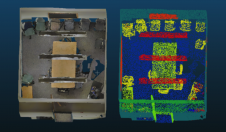

研究人员制定了务实的翻新政策的三种变体,并研究了东京不同地区的影响。“在此过程中,BIM-GIS集成对于以有效,整体,用户友好的方式组合数据至关重要,” Shinji Yamamura说。建筑信息建模(BIM)对于能源顾问和城市规划人员准备与建筑物相关的数据是必不可少的,可以将其与仿真软件结合使用,以预测建筑物内部或建筑物内部每项措施的效果。该能源模拟的城市基础架构数据来自本地地理信息系统(GIS)数据库。结果将返回到GIS平台上的3D城市模型,以检查其在城市或社区层面的效果。山穆拉及其同事开发的平台使能源管理运营商或地方政府工作人员能够可视化城市,地区或建筑物的能源消耗。在输入城市更新目标区域的位置之后,规划师不仅获得了城市计划信息和社区功能,而且还获得了可能最有效的能源技术包,并且需要进一步的模拟和分析。

Three package variations

Along one train line (East Japan Railway Company) in Tokyo, the researchers picked 12 communities which each have a train station at their centre. The GIS analysis combined with BIM databases from the urban planning department showed that there are a total of 150,000 buildings in those communities, 72% of which are small to medium-sized buildings. Only one community is made up of approximately 50% large buildings (over 50,000m2)。在12个社区中的三个中,建筑物用于商业或商业目的;其他九个是更多的居民区。

第一个选择是检查社区是否拥有超过5000万的建筑物2of floor space. The owners of these large buildings would be in a better position to raise the budget for low-energy renovation work than the owners of small and medium-sized buildings. Rigorously renovating the large buildings only in such a way that they consume over 60% less energy and leaving the small and medium-sized buildings as they are would produce around 18% energy savings across the whole community, concluded Nikken Sekkei Research Institute. “By using advanced technologies such as ZEB-ready methodologies, the large buildings can achieve that 60% reduction,” claims Yamamura. But it is expensive.

As the second alternative, the government should still stimulate renovation of all the large buildings, but more simply. The aim is for them to use 20% less energy. That is feasible with today’s more common technologies to reduce energy consumption in the field of isolation, lighting, cooling and heating. Simultaneously, all the small and medium- sized buildings should implement rather small and easy measures to reduce their energy consumption by only 10%: change to LED lighting, use slightly more efficient air-conditioning systems, etc. In this case, the community achieves 20% energy savings overall.

The third option is that half of the large buildings implement measures to save 20% and all the small and medium-sized buildings likewise save 20%. In that case, energy consumption is reduced by more than 27% for the whole area. To reach that goal, the same reduction steps as in the second renovation policy have to be taken and an area energy management system also has to be implemented. Using the cluster of computer-aided tools, the electricity grid operator optimises the performance of the energy generation and transmission systems.

Looking to the near future, Shinji Yamamura reveals: “The software platform we developed suggests the best-performing strategy, depending on the input from the BIM and GIS databases. Artificial intelligence (AI) can automatically design the optimised energy consumption communities; I am now developing such an AI-oriented tool.”

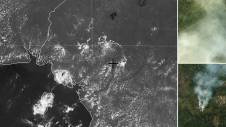

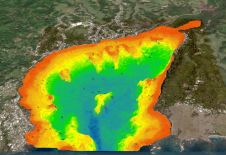

Heat island

BIM-GIS integration is useful in all kind of 3D simulations; Yamamura also uses it a lot for 3D-environment thermal simulations. Although only the energy-oriented issues are highlighted for the purpose of this article, this energy management technology can be part of a comprehensive system that includes the transportation system and urban design measures for heat island mitigation. Yamamura explains his vision: “It is part of a smart city concept with the aim to develop solutions simultaneously and widely at different levels. I believe that prevention of global warming and pursuit of comfortable living conditions are both realisable at the same time.”

When a government decides to invest in BIM-GIS integration, it has a multipurpose functionality in environmentally friendly design. Yamamura, who is also an expert on urban thermal environment planning, has advised on many‘cool city’ design projects that mitigate heat island phenomena in Japan and elsewhere in Asia. Microclimate plans with thermal environment simulations support municipalities in creating breeze corridors in city centres to alleviate the heat problem. The starting point is the same as with area energy management: neighbourhoods or districts must be seen as part of the whole system to achieve success at city level.

Shinji Yamamura and Nikken

Shinji Yamamura is executive officer and principal consultant with Nikken Sekkei Research Institute in Tokyo. He has a PhD in engineering and is a registered building mechanical and electrical engineer. Nikken Sekkei Research Institute was founded in 2006 and is one of the companies in the Nikken Sekkei Group (1950), providing a large variety of city planning, design and redevelopment services (2,600 employees). Its award-winning urban services can be seen throughout Japan, Russia, Asia and the Middle East.

Make your inbox more interesting.Add some geo.

Keep abreast of news, developments and technological advancement in the geomatics industry.

Sign up for free